The concept of Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM) was established, back in the 1930s, to address “optimal” water management, mainly from a technical perspective, but also taking into account social goals, such as the fulfillment of basic needs and the total welfare of the population. The chapter provides a comprehensive overview of issues related to IWRM. After a discussion of the various economic dimensions of water, we establish a basic model to analyze the value of water under different social welfare objective functions, including the human right to water. The technical-economic model also addresses questions of eco-hydrology, water recycling, groundwater management, and water quality management. The chapter also addresses water allocation along rivers and water transfers between watersheds. The chapter includes exercises and suggestions for further reading.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

The Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM) approach goes back to the establishment of the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) in the year 1933, which integrated the functions of navigation, flood control and power production (Biswas 2004). Further issues, such as erosion control, recreation and public health, were also addressed by the TVA (Mitchell 1990). The Secretary-General of the United Nations Organization (UNO) addressed the topic of IWRM in 1957. The UNO’s understanding of integration refers to supporting services needed to develop irrigated agriculture, but the coordination of different water-related functions was not part of this IWRM concept. This deficit was remedied at the Water Conference in Mar del Plata in 1977 where the necessity of coordination within the water sector was explicitly addressed. However, issues associated with high water demand and negative environmental impacts of irrigated agriculture were not approached sufficiently (Snellen and Schrevel 2004).

At the beginning of the 1990s, there were some observable shortcomings in traditional water management, like quality issues, overexploitation, ecosystem degradation or social concerns. Water problems also had become multidimensional, multi-sectoral, and multiregional and filled with multi-interests, multi-agendas, and multi-causes (Biswas 2004). To overcome these issues, four important guiding principles were determined during the International Conference on Environment and Water in Dublin in the year 1992 (Xie 2006). These principles (ecological, institutional, gender, economic) became well known as the “Dublin-Principles”, which are stated in the annex of this chapter.

The Dublin Guiding Principles represented an important input for the Agenda 21, which was agreed upon the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development in Rio de Janeiro in 1992. Chapter 18 emphasized the need for an integrated approach to manage water resources by connecting different water services and providing good governance, appropriate infrastructure, and sustainable financing. Footnote 1

The present understanding of IWRM with its holistic approach is strongly based on the Dublin-Principles as well as on the Agenda 21 (Chap. 18) document. There are many definitions of IWRM, for instance, in the Agenda 21. Footnote 2 A well-cited definition of IWRM is the one made by GWP (2000):

IWRM is a process which promotes the coordinated development and management of water, land and related resources in order to maximize the resultant economic and social welfare in an equitable manner without compromising the sustainability of vital ecosystems. Footnote 3

IWRM cannot be seen as a blueprint or product for good water management, but rather as a paradigm with a broad set of principles, tools, and guidelines that must be tailored to the specific context of a country, region, or river basin in order to implement an efficient and effective water resource management. A basic set of principles is outlined in Box 3.1.

Source: IWA/UNEP (2002)

The IWRM paradigm contains important key concepts of integration, decentralization, participation, and sustainability (Xie 2006). Due to the holistic view of the IWRM paradigm, there is a necessity for the integrated management of horizontal sectors that use or affect water resources, e.g., water supply, sanitation, agricultural use, energy generation, industrial use, or environmental protection. In addition to horizontal integration, vertical integration is also required to coordinate efforts between local, regional, national, and international water user groups and institutions (Xie 2006). The main aspects regarding natural system integration and human system integration are listed in detail in the chapter annex Sect. 3.13.2 (GWP 2000).

Besides the necessity of integration, there is also a need for decentralized decision-making and responsibility at the lowest effective management level, to increase awareness for local and regional problems. Hence, IWRM seeks to strike a balance between top-down and bottom-up management. IWRM also wants to strengthen community-based organizations and water user associations.

The consideration of sustainability, as a main part of IWRM, is not only restricted to ecological sustainability for protecting the natural system, but it also covers aspects of financial and economic sustainability. This means, for instance, that resource allocation decisions have to be based on the economic value of water. Therefore, water must be priced at its full costs (Xie 2006). Footnote 4

The three key policy goals of IWRM are Equity, Ecological integrity and Efficiency, which are known as the three’E’s (Postel 1992):

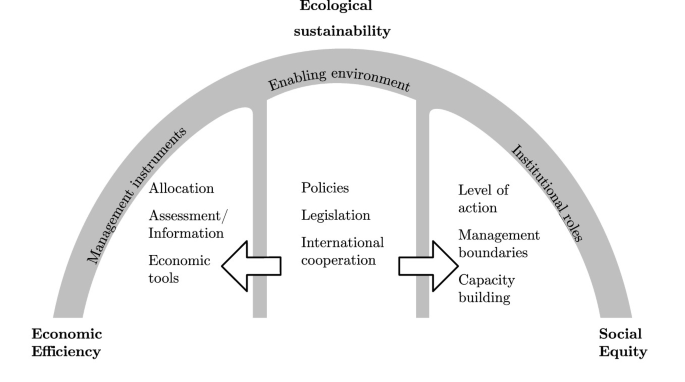

For supporting the application of IWRM principles in practice, the Global Water Partnership (GWP) has created a toolbox whose three main categories are an enabling environment, institutional roles, and management instruments (GWP 2000, 2004):

For transferring the IWRM paradigm into practice, the GWP (2004) recommends an IWRM planning cycle, which is illustrated in the chapter annex. In summary, the complexity of the water cycle and interdependencies within the water sector and other sectors (e.g., food sector, electricity sector) require specific methods for integrating environmental, social, and economic issues at the level of watersheds. The paradigm of IWRM provides us with the necessary interdisciplinary tools, which come from natural water science (e.g., hydrology, geohydrology, meteorology), engineering, and social sciences like political science, sociology, and economics. Often these methods, such as optimization models or decision supportive systems, etc., utilize mathematical models as a necessary prerequisite to capture complexity. Mathematically based hydro-economic models, which can be seen as a tool of IWRM, often work with simulation or optimization models and node-link networks to replicate the spatial distribution of important system elements like natural water bodies (e.g., sea, lake, aquifer, river section, etc.), artificial water bodies (e.g., canals, etc.), infrastructure (e.g., wells, dams, pipelines, pumps, purification plants, etc.), human/artificial impacts in the water system (e.g., point of use, point pollution source, non-point pollution source). Box 3.2 gives an example for a numerical-based hydro-economic model, which is extensively used, among other applications, to establish an IWRM approach in California (Fig. 3.1).

The CALVIN model is a numerical-based economic-engineering optimization model for water management in California. It was developed at the University of California in Davis. The data set contains a wide range of monthly parameters over the decades. The model is applicable to a variety of policy, operations, and planning problems. CALVIN manages water infrastructure and demands throughout California’s intertwined water network to minimize net scarcity and operating costs statewide. Some model applications are

Source: Howitt et al. (1999), Lund et al. (2009)

The following sections introduce general but simple models that cover the major problems of IWRM step-by-step. Specific topics and economic tools of IWRM, such as the pricing policy and transboundary river management, are also addressed.

If water is scarce then inevitably the economic perspective toward water gains a particular importance. This has been stated in the aforementioned declaration of Dublin. Principle 4 states that

water has an economic value in all its competing uses and should be recognized as an economic good. [. ] Managing water as an economic good is an important way of achieving efficient and equitable use, and of encouraging conservation and protection of water resources. (Xie 2006)

Emphasizing that water is an economic good does not imply this resource is exclusively a private good. Nor does it imply that water supply should be privatized. It simply implies that the water cycle must be managed as a nonabundant resource. The main difference of this kind of scarcity to other scarce goods, like e.g., precious old paintings or fossil fuels, is that scarcity is the result of a political decision not to overexploit the water cycle. The acknowledgment of scarcity follows from the adherence to the principle of sustainability. This statement is open with respect to the institutional implementation of the necessary management steps to assure sustainability and economic efficiency as well. In the following subsection, we analyze the various functions of the water cycle from an economic perspective.

One could imagine that water is collectively owned by a society. There are many examples worldwide of collectively owned and managed watersheds. For instance, Ostrom (1990) reports from irrigation cooperatives in Spain and the Philippines where the allotment of irrigation water has been fixed within a collective institutional setting that contains conflict resolution mechanisms as well as monitoring systems. On the other hand, there exist market-based solutions like water market institutions in the southwest of the the USA or in Australia. There, water is often owned privately according to traditional property rights and sold in spot and forward markets (see Chap. 5). Hence, saying that water is an economic good should not be confounded with the notion of water as a private good. A private good is characterized by its rivalness and by the possibility of exclusion on the basis of property rights. For example, if farmer A irrigates his fields the same water needed is not available for farmer B (rivalness). But the usage of water by farmer A requires also that he is able to get hold of this water (exclusion of other users).

But water appears not only as a private good. Indeed, the water cycle assures the livelihood of people in a watershed by satisfying many different life-supporting ecosystem functions. For environmental economists, the ecosystem functions of the water cycle interact with functions from other natural resources (soil, nutrients, vegetation, etc.), i.e., input factors that produce the total ecosystem to the inhabitants of a watershed. These ecosystem services lead to societal benefits, as they create economic value. As an example, a wetland mitigates flood damages and, at the same time, can be used as a recreational area. Forests contribute to the recharge of groundwater and influence the microclimate through evapotranspiration in a favorable manner. From an economic standpoint, these life-support functions represent societal and economic values far beyond, e.g., the plain use value of water for irrigation or for the water supply of households respectively.

Some of the ecosystem services of water mentioned above appear as public goods. Public goods are characterized by the absence of rivalness and the non-applicability of exclusion. The local water cycle, for instance, sustains the microclimatic stabilization of the watershed which is the base of livelihood for the inhabitants. All members of that local population reap this positive ecosystem function (non-rivalness) and nobody can be excluded (nonexclusion). Or take the example of the flood protection capability of a forest habitat or from a wetland. Here again, the advantage accrues to all neighbors sheltered. Table 3.1 shows the classification of natural resources and their services into different types of economic goods. Each of these types will require a specific approach of management to assure an efficient and environmentally sustainable supply to society.

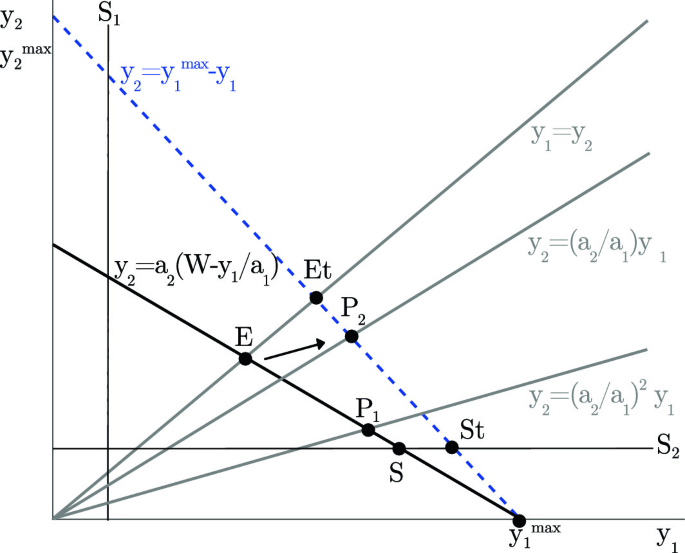

The four principles can be summarized with the help of Fig. 3.2. The production possibility line shows all possible combinations of output, \(\,y_\>\) , as a function of the water allocation, W. The maximum potential output of F1, \(y_^\) , is reached if the whole sustainable water supply, \(\bar\) , is allocated to F1, hence the output combination \(\left\< y_^,0\right\> \) satisfies the efficiency principle. The dotted line depicts all possible output distributions if a transfer system is available. In this case, the \(y_=a_ \bar \) will be distributed among F1 and F2 according to one of the fairness criteria. For strict equality we have point Et. Here, both farmers receive the same amount of agricultural output after the transfer has taken place. If one applies the accountability criterion, the output allocation is determined by proportional rule \(y_=[a_/(a_ + a_ )]y_^ \) . This allocation determines the proportion of both allocations, i.e., \(y_= (a_/a_)y_\) . The intersection of this array with the production possibility line (dotted line) is point P2 that defines the allocation for this case. Alternatively, the proportional rule can be applied to total water available, i.e., \(y_=[a_/(a_ + a_)]\bar\) , which leads to the array \(y_= (a_/a_)^y_\) . Footnote 9 Which of the two rules should be applied depends on what the distributandum is, water or agricultural output. Points S and St indicate the distribution if the basic need principle is satisfied.

If the institutional framework does not permit a redistribution of goods, the consideration of a fair distribution is only possible with the help of water allocation. In this case, the production possibility line is given by the solid line in Fig. 3.2. The corresponding allocations are then given by the points E (strict equality), P1 (proportional allocation) and S (basic needs). The lines \(S_\) and \(S_\) are the respective lifelines of F2 and F1, i.e., the minimum outputs that are sufficient for survival. Moving from S to St illustrates the institutional efficiency gains that can be realized by introducing a transfer system.

The difference principle of John Rawls is visualized by the shift from E to, say, P2. If in the course of an institutional innovation transfers are introduced we could move from the strict egalitarian distribution E to P2 for instance. Footnote 10 In point P2 both incomes in terms of output quantities have increased relative to point E, therefore the difference principle is satisfied despite the deterioration of the income distribution among the users. The increase in income of F1 is accompanied by a rise in F2’s income. P2 is the allocation point where the accountability principle is satisfied. Here, total output, \(y_^ \) , is divided proportionally in shares of \(a_/(a_+a_) \) . If transfers are not possible, the accountability principle can only be applied to the water allocation. In this case allocation P1 will be chosen.

In mathematical policy models, the optimal allocation is often derived from a social welfare function (SWF). Usually, these functions depend on the utility or the well-being of every single member of the community or society under consideration. In our simple case, the social welfare function could be written as \(SWF = G(y_,y_)\) . The well-being of F1 and F2 is indicated by their incomes, \(y_\) and \(y_\) , respectively. There are various specifications of this function that can be related to the fairness principles introduced above. The SWF most prevalent in economics and also in the IWRM literature is the so-called utilitarian social welfare function, according to which social welfare is simply the sum of the individual welfare of every single member of the society. Here, individual welfare is identified as an individual’s income and its consumption.

$$\beginThe optimal allocation of water is derived by maximizing the objective function represented by Eq. (3.1) while taking all the economic and hydrological constraints into account. This SWF adheres to the efficiency principle. What matters is the total sum of individuals’ well-being without any regard of the distribution of well-being. If we insert the farmers’ linear production functions into Eq. (3.1) and stick to a an ecologically sustainable solution the management’s objective is

$$\beginUtilizing the Karush–Kuhn–Tucker (KKT) conditions Footnote 11 we get the solution \(w_^= \bar\) and \(w_^= 0\) . All the water goes to F1 leading to consumption of \(y_^= a_\bar\) and \(y_^=0\) .

However, as this allocation can hardly be termed fair, the program can be amended by additional constraints to include the various fairness principles. For instance, if we include the restriction of a minimum threshold for F2’s consumption quantities, i.e., \(y_ \ge s_\) , the program would lead to a water allocation such that point S, or point St in the case a transfer system is in place, will be reached. The allocations in points S and St satisfy the basic need principle. Or you believe in the principle of strict equality. Then, the additional constraint to be included in the maximization program is \(y_= y_\) , which leads to a solution indicated by point E. In the presence of a transfer system, we must include \(a_ w_ - \tau = a_ w_ + \tau \) where \(\tau \) is the transfer from F1 to F2, yielding the solution in point Et. The adherence to strict equality can be expressed by a Social Welfare Function (SWF), which states that the well-being of society depends exclusively on the well-being of the most disadvantaged individual.

$$\beginMaximizing this SWF leads, of course, to an egalitarian solution, as depicted by points E and Et in Fig. 3.2. This SWF represents Rawls’ difference principle, as the only criterion determining overall social welfare is the well-being of the poor. If in the course of an increase in income of the more advantaged, the income of the poor rises as well, social welfare has improved. The social improvement comes through the income increase of the poor, not through the increase of both incomes as in the case of the utilitarian SWF.

Thus far we have identified income or consumption as well-being. The allocation problem becomes more complicated if well-being is not directly expressed by income or consumption but by the utility these observable variables create. Thereby, the level of well-being does not follow consumption in a linear manner generally. Doubling consumption leads to less than doubling of the original satisfaction level. Footnote 12 Furthermore, this attitude toward consumption differs individually.

The level of satisfaction resulting from consumption can be expressed by means of a utility function that transforms consumption quantities into some utilitarian units of well-being or happiness. Footnote 13 Let us assume that the utility functions of F1 and F2, respectively, are

$$\beginThe heterogeneity of both farmers is indicated by the two parameters A and B, where we assume that \(A

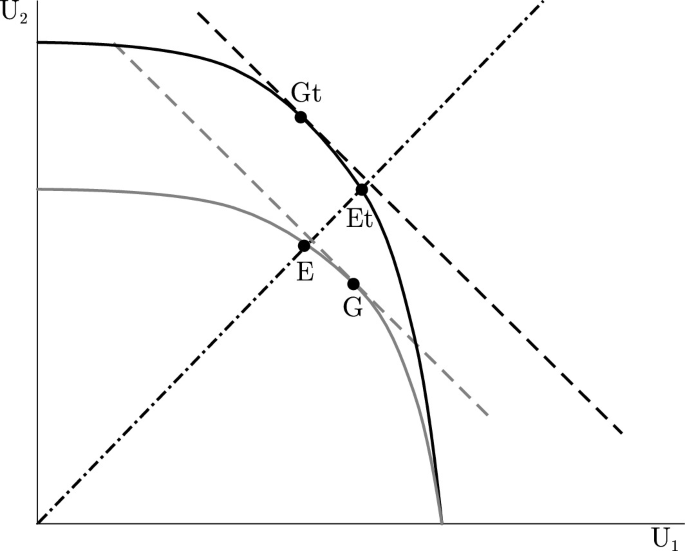

Similar to the production possibility frontier, we can construct a utility possibility frontier indicating all possible utility distributions that can be achieved by allocating water to F1 and F2. Recall that \(w_= \bar - w_\) , which is substituted in Eq. (3.5). Solving Eq. (3.4) for \(w_\) gives \(w_= (B_/A)^<(1/\eta )>\) and inserting this expression for \(w_\) into Eq. (3.5) yields

$$\beginEquation (3.6) is the algebraic specification of the utility possibility frontier. Note that this frontier is derived under the assumption that transfers of output between both farmers are not possible. In Fig. 3.3, it corresponds to the lower of the two convex curves.

If output transfers are assumed to be feasible the derivation of the utility possibility frontier consists of two steps. First, total output is maximized by allocating all water to F1, such that \(y_^ = a_\bar\) . Second, the (re-)distribution of utility from F1 and F2 can indirectly be accomplished by an output transfer, \(\tau \) , such that

$$\beginSolving Eq. (3.7) for \(\tau \) and inserting the expression into Eq. (3.8) yields the utility possibility frontier for the case that a transfer system can be established.

$$\beginThis function is also displayed in Fig. 3.3 (the upper convex curve). Both utility frontiers, which assume either the impossibility of output transfers or the availability of a transfer mechanism, present the maximum utility level of F2 given the utility level of F1.

The lower (light gray) possibility curve represents all utility distributions when transfers are not possible, thus F2 can only acquire utility by producing at his site. To do so, water has to be diverted from the more productive farmer F1 to F2. Hence, the choice of the utility distribution among both farmers cannot be separated from the choice of the “size of the cake”. However, if an output transfer system can be installed the issues of maximizing agricultural output and of output distribution can be separated.

Figure 3.3 plots as the first proposal the equal distribution of well-being. The 45-degree line through the origin shows this equal distribution. There is one intersection with each of the two utility possibility curves. The first one is E. Here, water has to be allocated such that both farmers are equally well off. Since no transfers are possible the water allocation has to solve both tasks, production efficiency and fair distribution.

The second intersection ist Et where equality of utility is ensured. Here, the issue of distribution can be separated from the water allocation. Since F1 is more productive than F2, all water gos to F1. However, the output is distributed such that equality of well-being is achieved. Since F1 derives less utility from consumption than F2 does, F1 requires more quantities consumed than F2 in order to achieve the same level of utility for both farmers. From \(U_(y_) = U_(y_)\) it follows

$$\beginOf course, to perform this calculation we must be able to compare the utilities of both farmers, i.e., interpersonal comparability must be possible. This requires a certain degree of measurability of happiness or well-being. If this is given we can not only determine the optimal total output but also its distribution according to the utility created for both farmers. This must not necessarily be the equal well-being solution, which we just have discussed. This may also depend on other fairness principles to which the policy maker or the community adheres.

Dating back to Jeremy Bentham, a philosopher of the eighteenth century, the main goal of a free society should be to organize the economy such that it leads to the “Greatest happiness of the greatest number” (Bentham 2008, 393). Societal welfare is defined as the sum over all individual levels of well-being. The corresponding SWF is simply the utilitarian specification, as in Eq. (3.2). The income distribution matters only insofar as it contributes to achieving the goal of the greatest happiness of all members.

Again, we have to distinguish between a system without and with transfer possibilities. In the case with no transfer, the optimal water allocation can be determined by maximizing the sum of utilities, i.e., \(U_ = U_+U_ \) . Graphically, this will be achieved in Fig. 3.3 at point G southeast of E. Here, \(U_\) reaches the highest value possible in an allocation system without transfer. Footnote 15 The resulting benefit distribution is not equal. The amount of water is distributed in an inequitable way. F1 receives more than F2. This result depends on two countervailing effects. On one side, F2 should receive more consumption due to its higher marginal utility, on the other side F2 is less productive than F1. Hence, shifting more water to F2 decreases total well-being. Footnote 16 It can thus be seen that Bentham’s approach does indeed advocate inequality if it only leads to a maximization of aggregated well-being.

The corresponding water allocation point G is based on is calculated from the following program:

$$\beginThe exact determination of this allocation is not necessary here. It is sufficient to see that Bentham’s utilitarian approach subordinates the distribution of benefits to the criterion of aggregated welfare. As a result, the available water is allocated such that point G is realized.

In case of a system with transfer, we get a similar result. The Benthamian solution is determined graphically as in the first case. We move the line of the total benefit up to the right until we touch the outermost point Gt in Fig. 3.3. The algebraic solution is derived as follows: We start by allocating all water to F1 (see program Eq. (3.12)) and maximize total utility with respect to a transfer variable:

$$\beginFrom the optimality condition \(U'_(..)= U'_(..)\) , we can derive

Since \(A= \left( a_ \bar - \tau \right) < \tau = y_\) . Contrary to the allocation under strict equality, F1 gets less income than F2, simply because farmer F1 is less effective in terms of generating well-being through his low valuing of consumption. Thus, point Gt is northwest of point Et. If one compares both solutions, the egalitarian and the utilitarian in Fig. 3.3, one can observe that in point Gt total utility is maximized, whereas in Et total utility is below its maximum value. The utilitarian criterion is achieved at the expense of that member of society who derives less utility from consumption. Footnote 17 If one adheres to the concept of moral arbitrariness this approach is not convincing. If the intensity of consumption pleasure is innate, then it is collectively owned by the society. Hence, the marginal utility of income attached by nature to the members of the society does not imply an entitlement to more consumption. As such, equating marginal utilities so as to maximize the SFW is morally not convincing in the view of supporters of an egalitarian standpoint.

From a practical viewpoint, it is important to note that distributional issues can be separated from efficiency problems only as far as the society is equipped with the necessary institutional capacities to solve distributional requirements with instruments other than the allocation of inputs and products. In our example, irrespective of the distributional principles the water allocation was chosen by directing the whole water available to farmer F1. Many integrated water management models start from this separability assumption focusing solely on the allocation of water and other inputs while leaving distributional issues to social and distribution policy. If water is used for different purposes, e.g., as input for agricultural products and as a consumption good for households the separation of distributional and allocational issues gets more complicated. Needless to say that the weighing of distributive and allocative issues is a major challenge in the specific institutional environment, and that solutions must be tailored specific to the context, too.

So far it was assumed that no abstraction costs incur to both farmers. Without costs, the use of water could be infinite if it was not constrained by the upper bound \(\bar \) . If such a constraint cannot be implemented, water will be overused. However, if abstraction costs are present water overuse can be prevented or at least lessened. To analyze the relation among water utilization, abstraction costs, and sustainability thresholds, we include abstraction costs in our two-farmer model. Furthermore, it is assumed that production of the agricultural product can be captured by the production functions depicted in Eqs. (3.14) and (3.15).

$$\beginInstead of assuming that one farmer is always more productive than the other, we now introduce production functions with decreasing marginal products. For simplicity both farmers differ only with respect to \(a_\) , where \(a_>a_\) . Costs of water abstraction denominated in agricultural products are determined by the cost functions in Eq. (3.16), where F denotes the fixed cost and c the marginal cost of abstracting water.

$$\beginDisregarding distributional issues, the goal is to maximize the aggregated output of agricultural products, i.e.,

$$\beginleading to the optimality conditions

$$\beginThis allocation can also be achieved in a market economy, where farmers maximize their profits according to

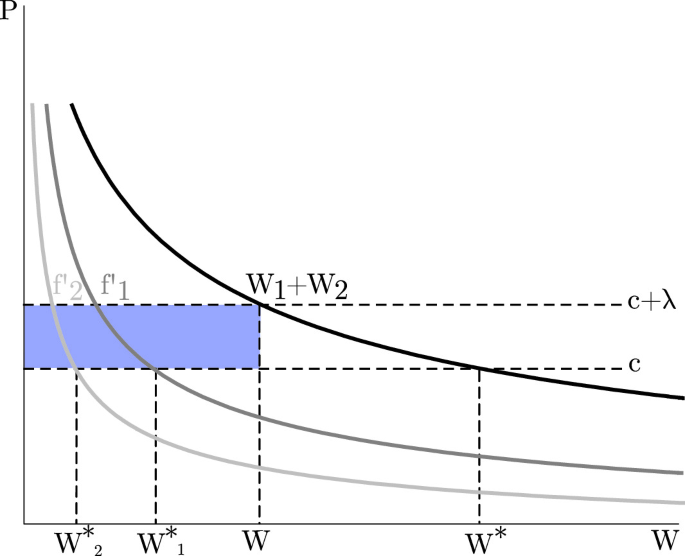

and a water treatment plant sells water under a price regulation scheme. The price scheme for both farmers is a two-part tariff consisting of a volumetric component q and an access fee M. The price regulation authority sets \(q= c\) and \(M=F/2\) . From Eq. (3.19), it is obvious that the market equilibrium together with the water price regulation leads to the optimal allocation. Total amount of water used, \(w_^+w_^= W^\) , is determined in Fig. 3.4, where the total demand curve intersects with the constant marginal cost line. The intersections of the respective marginal product curves of each farmer with the marginal cost line yield the optimal allocation.

Since it is costly to abstract water, its use is finite. It remains to examine whether the optimal allocation, \(W^\) , lies above the sustainable boundary, \(\bar\) . In Fig. 3.4, two scenarios are depicted. The first scenario assumes that aggregated water use is less than the sustainability boundary leading to a water price of \(q=c\) . The second scenario assumes that abstracting water is sufficiently cheap such that the aggregated water use of both farmers exceeds the sustainable boundary. In this case, the presence of abstraction costs does not protect the hydrological cycle sufficiently. Hence, a hydrological constraint must be introduced leading to the optimization program

$$\beginThis leads to the optimality conditions

$$\beginwhere \(\lambda > 0\) is the respective Lagrangian of the constraint. This case is depicted in Fig. 3.4, where total water demand is constrained by the black line of \(\bar\) . As a result, the marginal products exceed marginal cost by the difference which is called scarcity rent.

Consider the respective market solution. The regulatory authority must increase the volumetric component of the water tariff to \(q= c + \lambda \) in order to push back total demand such that it does not exceed the sustainability threshold. Since the sustainable water supply is smaller than the amount of water that the economy would abstract, water is scarce and, as a consequence, the water price exceeds marginal costs, which yields a scarcity rent for the water supplier. Figure 3.4 shows the income of the water supplier due to the scarcity rent, which is represented by the shaded rectangular. There is a discussion about the distribution of the scarcity rent. Footnote 18 This rent income can be used to lower the access fee. But what should we do with residual (if there is one)? Some people suggest that this rent income should be taxed away and redistributed to the users. Or they take the existence of scarcity rents as an argument to claim that the water infrastructure must be owned publicly.

Alan Garcia, former president of Peru, complained that the country is poor despite its abundance of natural resources. According to the Human Development Index (HDI), Peru ranges at position 77 out of 187 countries. The HDI is an aggregated measure for the living conditions of a country with respect to life expectancy, access to knowledge and a decent standard of living. Alan Garcia identified political and cultural traits as the very source of this deplorable economic and social situation, which he referred to as the dog-in-the-manger-syndrome. The dog in the manger is a figure from a fable of the ancient storyteller Aesop. The beast lies in the manger full of straw and prevents other animals to take the straw from the manger. The very motive is a pure grudge, as the straw is useless to the dog. Translated into the Peruvian political environment, the dog can be seen as an analogy for poor peasants dwelling on small plots in the countryside without any access to agricultural technology and, at the same time, lacking the financial means to invest. In addition, property rights are informal thus making investments insecure. Whenever modern politicians tried to develop the traditional agriculture by consolidating the plots into plains accessible to agricultural technology, local uproar emanated, often well organized by local politicians. According to Alan Garcia, people were caught in a vicious circle of poverty and an ideological superstructure that left them in a habitual state of hostility toward modern development.

There were some attempts to modernize the agricultural sector by promoting privatization and land consolidation with the help of law amendments and even new laws. In 2009, the Peruvian parliament passed a water bill that put much emphasis on the efficient use of water. The water irrigation system of traditional agriculture was highly inefficient compared to modern technologies based on, e.g., drip irrigation. Therefore, a development framework plan was established up to attract large-scale agribusiness enterprises able to invest in efficiency-enhancing technologies. But there has been political resistance against this development agenda, which raises the question whether this opposition can only be interpreted as driven by the grudge of the dog in the manger. We can shed some light in this discussion with the help of our farmer model, thereby discussing the interrelation between water efficiency and income distribution.

Let us assume that there are n equally sized lots of land \(i = \ <1,2,\ldots ,n\>\) that are cropped in a traditional manner. The water productivity \(a_\) is equal across all lots (the subscript t refers to the traditional agricultural production). In addition, labor required per lot is \(l_= (1/b_) y_\) , where \(b_\) is labor productivity which is also equal across all lots. Each peasant gets the same amount of water \(w_=w_ \cdots = w_\) , where \(\sum w_ = \bar\) . Thus \(w_ = \bar/n, \, \forall i\) . Recall that \(y_ = a_ w_\) . Then, total labor required for the total agricultural product is

$$\beginwhere total output amounts to

$$\beginWe assume that in the outset there is no unemployment, i.e., the required amount of labor \(L_\) equals the number of peasants or land laborers dwelling on the site. Production and income per peasant (laborer) is

$$\beginwhere the right-hand side follows from Eqs. (3.22) and (3.23), indicating that peasants earn their productivity.

A big investment project is proposed covering all n sites. Water productivity will increase to \(a_ > a_\) for all sites (The subscript m denotes modern agricultural technologies.). Consequently, output per site will increase to \(y_ = a_w_\) . Since each lot is equally productive, the water is allocated in equal portions, i.e., \( w_=w_=\cdots =w_\) , resulting in \(y_ = a_ \bar/n \) . Total agricultural output is \( Y_ = a_ \bar > Y_ = a_ \bar \) . The question remains whether there is enough labor available to produce \(Y_\) . Assume that the new technology makes labor also more productive due to the capital intensive cultivation of the the land, such that

$$\beginwhere \(b_ > b_\) . Both coefficients of the modern technology are higher, leaving the question whether the new technology is labor saving. Observations in many countries document that in the course of modernizing of the agricultural sector migration into cities can be observed, which indicates that agricultural technical progress is labor saving (Bhandari and Ghimire 2016). Therefore, we assume that \(L_ < L_\) .

It remains to analyze the total effect of technological progress in terms of poverty alleviation. Does the real income of peasants increase or decrease through modernizing agriculture?

Let us proceed with the analysis by introducing the investors: Profits of the investors are given by

$$\beginwhere w is the real wage. The labor demand function of the agro-business firm can be derived by maximizing its profits with respect to L. Since the model is linear, the demand function is a step function as depicted in the following figure below. If \(b_ \ge w \) , i.e., if labor productivity is not less than the real wage w, labor demand expands to \(L_=(a_/b_)\bar\) , which is the labor requirement to produce total output \(Y_\) , given a labor productivity of \(b_\) and water availability \(\bar\) . If the real wage exceeds \(b_\) , labor demand vanishes because the innovation is not profitable. The labor supply function is represented by the kinked curve in the following figure.

If real wage is higher than s, which can be interpreted as the alternative real income of the peasants leaving the countryside for employment opportunities in the urban area, all peasants \(L_\) want to stay employed in the agricultural sector. If we let both curves intersect, the equilibrium will exactly be equal to s, implying that the efficiency-enhancing technology leads to a drop in real income for the peasants from \(b_\) to s. Then, indeed, efficiency and distributional goals contradict.

But there are some other countervailing effects that might ease the situation of land laborers. The increased production of agricultural output from \(Y_\) to \(Y_\) may lead to a decrease in the price for these products, thus increasing the urban real wage s. If the price decline is such that \(s > b_\) , the poverty of the peasants is reduced. The occurrence of profits for agro-business firms leads to an increase for real wage and hence to a welfare increase for the least advantaged. But even if s falls short of \(b_\) it would be conceivable that poverty is reduced. If the poor peasants became shareholders of the firm their welfare would increase above \(b_\) . But this requires well-defined property rights allowing peasants to sell their sites in exchange for those shares. If property rights are not well defined and well protected by sustainable institutions, it may also happen that peasants are simply expropriated (the blue intersection point in the figure). The dog in the manger knows why he defies modernization.

In summary, the political discussion of modernizing traditional production structures in the agriculture of developing countries cannot be based solely on efficiency considerations. IWRM shall not neglect the redistributive effects of efficiency-enhancing measures.

Sources: Cohen and Weitzman (1975), Boelens and Vos (2012), Bhandari and Ghimire (2016)

The water cycle provides not only water as a consumption good to consumers or as a productive input to firms but it is also indispensable for environmental services like the production of vapor that stabilizes the microclimate. Or take the ecological system of water and forests as an example. Forests produce ecosystem services like flood control, water filtration, or provision of habitats for various species, whereas in turn forests need land and water. The water cycle is a fundamental part of the whole eco-system. This ecological system consists of various natural cycles which are interlinked. Footnote 19 In addition to the hydrological cycle, we have the carbon-oxygen cycle that consists of a photosynthesis part, in which carbon dioxide is converted into oxygen, and the decomposition part, where organic molecules are separated into carbon dioxide and water. There is also a nitrogen cycle that is crucial for the growth and decay cycle of plants. On an ecological level, these cycles form the nutrient cycles where all the different living systems take place. From a more holistic IWRM viewpoint, these cycles are affected by the shaping of the local hydrological cycle and the way land use is organized. Some scientists, therefore, claim that all these interactions have to be included in a comprehensive policy approach.

A management system following this holistic integrated approach is called ecohydrology, a term introduced by Rodriguez-Iturbe (2000). It comprises the whole climate-soil-vegetation system. Thus, landscape planning and the management of water resources have to be closely linked. In this sense, IWRM goes far beyond the efficient provision of water for the private consumption of households or firms. The economic management of a river has not only to organize the abstraction of water but also to secure the water provision for the local ecosystem services. These services are sustained by assuring the viability of the various ecological cycles mentioned above. Also, these services include also more visible services, e.g., the provision of recreation in the form of, e.g., fishing, hiking, camping, or the mere presence of nature as an acoustical and visual environment that is part of the cultural landscape.

Under this perspective, we note that IWRM is much more than only managing some water flows for private use. From an economic perspective it turns out that water management, which takes these eco-services into account, considers water not only as a private but also as a public good. For instance, the stabilization of the microclimate by the water cycle is an ecosystem service that affects all inhabitants of a watershed (and beyond). In the following, we include this public good property of water into our IWRM approach. To do so we utilize our hydro-economic model introduced in Sect. 2.3.

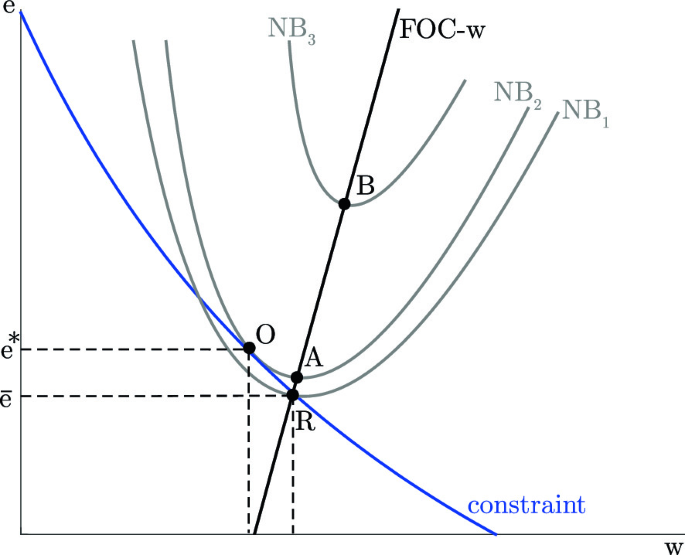

Assume that there are two options for water management. Either water is abstracted for private purposes or water is retained for the ecosystem. To keep the analysis simple, we assume that the value of ecosystem services can be captured by a utility function \(U_(E), i=\<1,2,\ldots ,n\>\) that depends on these services. i is the index of individual i and n is the size of the population living in the watershed. E are the ecosystem services, i.e., the parameter contains the whole interdependency between the water cycle, the vegetation, and the geological structure of the watershed. Footnote 20 E depends not only on policy instruments of the IWRM but also on other economic variables that influence the ecosystem shaping the landscape (e.g., soil sealing, agricultural vegetation, . ). In the following, we focus solely on the issue of allocating water to private purposes and to public services. We identify the green water, i.e., the evapotranspiration of the vegetation, as a public good, because all inhabitants are affected similarly by the vapor of green water. Thus, the utility function for ecosystem services depends on the evapotranspiration, ET, as depicted in Eq. (3.27).

$$\beginThe benefit of private water consumption is represented by a benefit function, \(B_\) , Footnote 21 that represents profits or benefit from water consumption

$$\beginThe hydrology can be captured by our linear dynamic mass equation

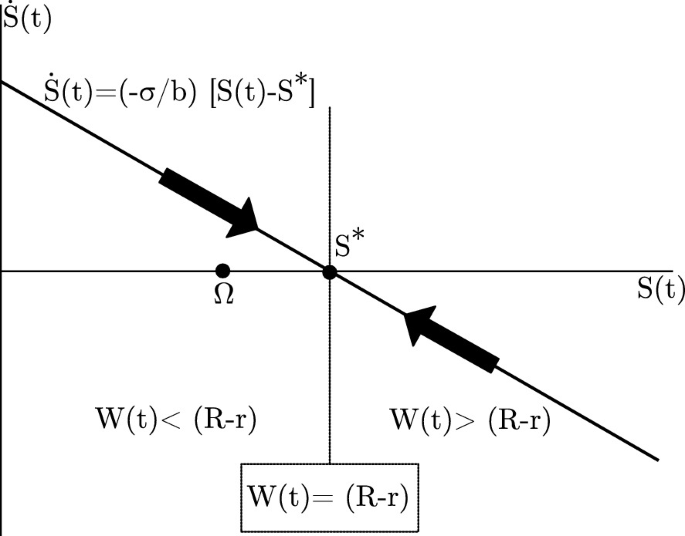

$$\beginTo keep the optimization procedure simple, we confine ourselves to a steady-state analysis, i.e., we assume that the local hydrological cycle is an equilibrium where \(dS(t)/dt = 0 \) . Solving for S, we get

$$\beginThe equation shows that S depends on the water allocation to consumers, \(w_\) with \(i=\ <1,2,\ldots ,n\>\) . To solve the IWRM problem, the definition of the social welfare function is required and presented in Eq. (3.31).

$$\beginThe management task is to maximize SWF with respect to \(w_\) taking into account that private consumption reduces water available for the ecosystem (see Eq. (3.30)). It is a straightforward exercise to derive the optimality conditions for each individual:

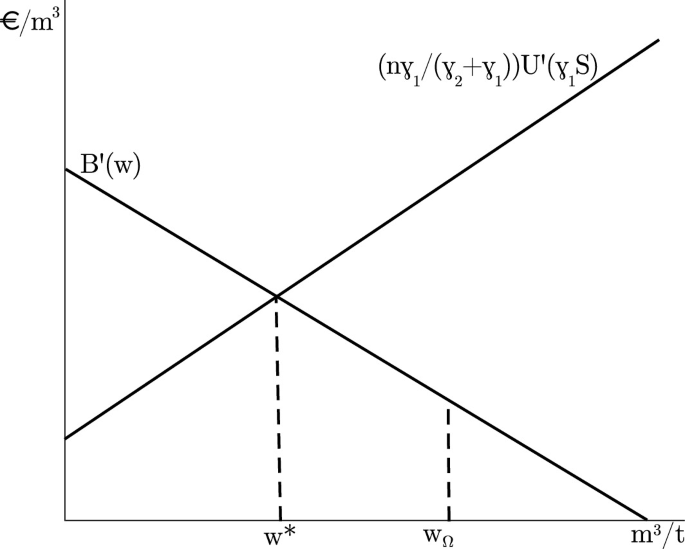

$$\beginwhere S is represented by Eq. (3.30). This set of equations reflects the Samuelson-rule that specifies how the optimal amount of a public good should be determined. The main point is that private marginal benefit should be equal to the sum of marginal benefits over all inhabitants, as one liter of private water consumption is associated with costs that stem from the marginal loss of ecosystem services for all inhabitants. Hence, both values must be optimally balanced. If we assume that all inhabitants are identical with respect to their valuation functions we can condense the set of equations into one figure. Notice that in this case Eq. (3.32) reduces to

$$\beginwhere S is defined in Eq. (3.30) (Fig. 3.5).

The optimal water consumption is where both marginal valuation curves intersect. Inserting \(w^ \) into Eq. (3.30) yields the optimal stream of green water, ET, the optimal evapotranspiration, which interacts with all the other natural cycle mentioned above. As a result, a micro-climate is established that sustains environmental services leading to the well-being of the local human population. Depending on cultural traits and also on the population size, this intersection of marginal valuation curves can change over time, i.e., \(w^\) can change and move to the right, for example. There is a certain viable range of \(\\) -combinations the water management can choose. Landscapes can be shaped in many various ways depending on cultural traditions and, of course, the biological needs of the society. However, there are boundaries. Beyond these boundaries, irreversible changes in the ecology will take place. As a result, by transgressing these ecological tipping points, the regional ecological system might switch into a state hostile to human life, like a desert for instance. This boundary is depicted in Fig. 3.5 as \(w_ \) . If water abstraction is higher than this tipping point, evapotranspiration decreases to an extent that triggers a complete change of the microclimate. The ecological system turns into a semiarid or arid zone with all the detrimental consequences for society. Footnote 22

According to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the World Health Organization (WHO 2019), more than two billion people in the world did not have access to safe drinking water, and another two billion people lacked access to basic sanitation in 2019. In 2010, the UN General Assembly declared the access to water, be it as drinking water or a medium for sanitation and hygiene, as a human right. Together with six additional goals, which range from halving the proportion of people living in extreme poverty to reducing the under-five mortality rate by two-thirds between 1990 and 2015, the Millennium Goal 7 called to Footnote 23

Halve, by 2015, the proportion of the population without sustainable access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation.

In 2015, these Millennium Development Goals were replaced by the Sustainable Development Goals consisting of 17 goals ranging from poverty and hunger eradication to strategies aiming at building peaceful and inclusive institutions. Goal 6 refers to clean water and sanitation, according to which universal access to safe and affordable drinking water should be ensured by 2030—quite an ambitious goal in the face of climate change leading to water scarcity, specifically in those areas of the world with the poorest inhabitants.

From the perspective of IWRM, the achievement of Goal 6 requires to tackle the access problem and, at the same time, to protect the catchment areas against an overutilization of water. Water scarcity translates into high water prices, which in turn brings about an optimal allocation of water use. This approach will only result in an optimal equilibrium if all market participants can afford the amount of water to cover their basic needs for a secure conduct of life. There is a broad literature on basic water needs, the lower range of which would be in the range of 15 liters per day and capita (lpd) (Reed et al. 2011). This lifeline is subdivided into various need types as displayed in Table 3.3.

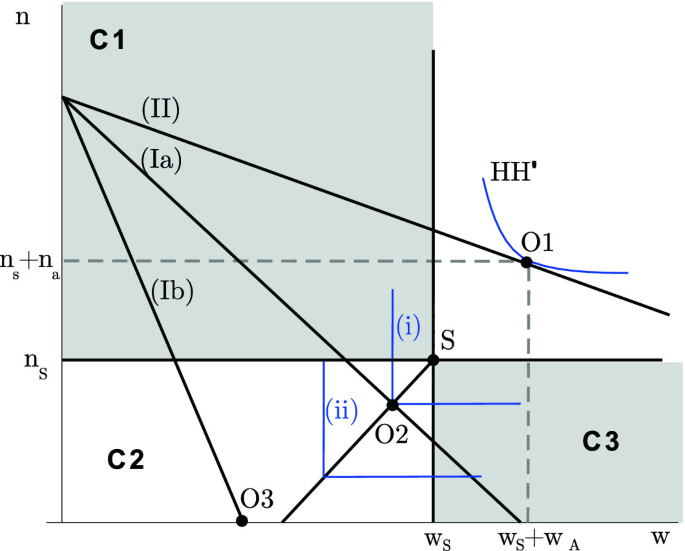

Contrary to the standard household model, we distinguish between consumption which satisfies the first layer of needs \(\,n_\> \) and additional consumption which serves the cultural needs, i.e.,

$$\beginThe optimal point O1 can be derived with the help of the standard maximization approach for households.

$$\beginFigure 3.6 also depicts two further scenarios, which refer to the case that the households income does not suffice to cover the subsistence point S, i.e., the point where both goods can be purchased in an amount that guarantees the full coverage of the physical needs. Footnote 25 These are the areas C1, C2, and C3.

Here, a survival strategy is required. Poor households try to maximize their life expectancy or survival probability with the help of a household production function. This production function transforms the inputs water and basic goods into a certain health state, which can be expressed in, say, survival probability units. Similar to ordinary indifference curves derived from standard utility functions, iso-health lines can be defined with increasing survival probability to the northeast and decreasing life expectancy to the southwest. There are various possible shapes to draw these iso-health lines. We assume for simplicity that these lines follow from a linear-limitational interrelation. Let the corresponding survival function be

$$\beginwhere \(a, b, g >0\) are parameters determining the slope and the position of the expansion path connecting all corner points for various iso-health lines. As water is more important than nutrition to survive for a certain time we have assumed that the expansion path intersects the abscissa at a positive \(w_\) -value. The expansion path, i.e., the line connecting all corner points of iso-health lines shows how households react optimally if income decreases and/or relative prices change. Assume, for instance, that the budget line (II) rotates to the southwest because the price of water has increased (line Ia). Households try to maximize their health by maximizing \(S(w_,n_)\) subject to their budget line Ia, i.e., \( y = p_ w_ + p_ n_ \) . The optimal need management then leads to point O2. As the water price increases more and more, the optimal point shifts to the southwest finally reaching the horizontal axis for budget line Ib. From there, the optimum point moves along the horizontal axis and towards the origin, i.e., the household tries to use all its income for buying water (see point O3).

The specification of the survival function needs more empirical investigation. Note, however, that the main point of this model does not rest on the precise structure of iso-health lines but on the viewpoint that the extremely poor can only choose their water and basic food southwest of the point S. Whatever quantities \(w_\) and \(n_\) are chosen by poor households, they cannot be interpreted as instruments used to maximize well-being in the sense of an optimal management of tastes and preferences that are relevant for the upper layers of the Maslowian hierarchy. They simply represent rational survival strategies.

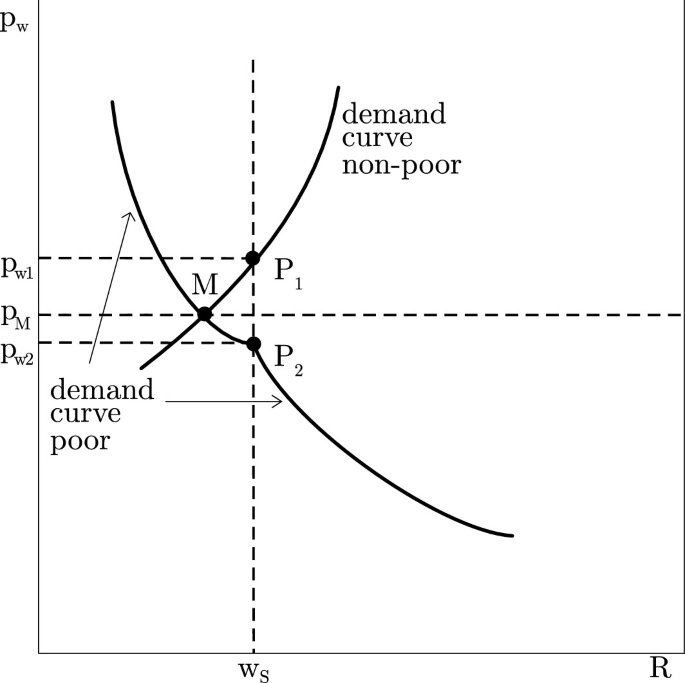

Now we are able to construct the water demand curve of poor households beginning from a price that leaves the consumption bundle in the area of needs and preferences beyond pure survival. If \(p_\) increases, finally demand will reach \(w_ \) . From there on the water consumption decreases with increasing price ever further exhibiting an optimal survival strategy (expansion path \(S-O2-O3\) ). The demand curve consisting of the two parts is drawn in Fig. 3.7 from left to right. A demand curve of a second household with a higher income is drawn from right to left. This household receives such a high income that he does not get into the critical survival zone.

Supply costs are not included so as to keep the figure clearly laid out. We simply assume that there is a certain amount of water (R) given. Hence, the equilibrium water price \(p_\) equilibrating demand supply (point M) is a scarcity rent. In this equilibrium point, demand and supply are equal. The water available is allocated to both households according to their marginal willingness to pay (demand curves). However, the equilibrium does not result in a social optimum. Footnote 26 Obviously, the poor household operates in the survival zone and, hence, the Sustainable Development Goals are not satisfied. The market mechanism transfers too much burden to the poor due to the scarcity of water.

There are various options to secure the lifeline of the poor. One option is to introduce price discrimination. In Fig. 3.7, the high-income water demand is charged with a higher price, \(p_\) , and the poor households pay a lower price, \(p_\) . This type of price discrimination can be achieved, for example, by an increasing block tariff structure which will be presented and analyzed in depth in Chap. 4. Theoretically, another option is to subsidize the poor directly. In this case, price discrimination can be abandoned and a unique market price can prevail since poor households receive a lump sum transfer that lifts their income such that they can afford the subsistence point S.

Water scarcity, major driver for water reuse, has been called the challenge of the twenty-first century (Miller 2006). Before we look more closely on the different types of water reuse, let us define the terminology:

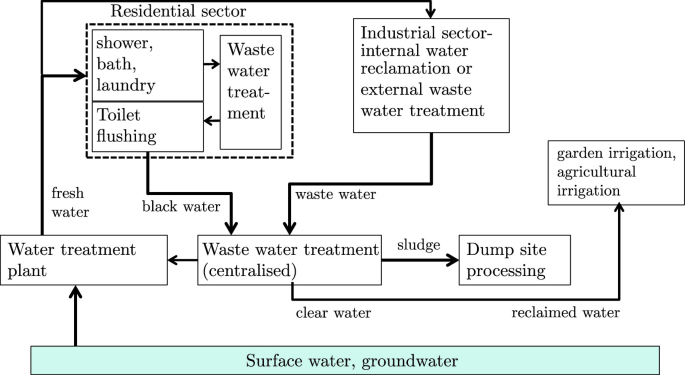

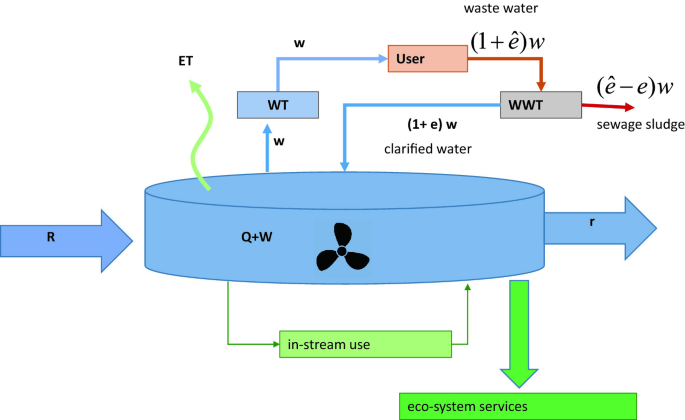

Figure 3.8 depicts the various flows of wastewater release, reclamation modes and reuse for the residential and industrial sector. It shows that water reuse is also part of the water cycle.

Singapore is a highly urbanized city-state. The city is characterized by a very high population density. Hence, the water demand for this state can only be met by an area several times its size, if only conventional water resources are used. For becoming more independent from water imports from Malaysia, Singapore enforces the development of innovative water technologies, e.g., desalination, but also recycling of water. Reclaimed water is an important water source in Singapore which can be produced in an innovative way. Here, the wastewater is treated using membrane filtration and reverse osmosis. The generated freshwater, after all purification steps, meets the standards of potable water. This procedure of water supply management became known under the brand name NEWater. The predominant share of the reclaimed water is used in the industry sector mainly for non-potable applications. But about 1 percent of Singapore’s potable water requirement is covered with reclaimed water from the NEWater project, too.

Source: Tortajada (2012)

IWRM requires to consider all available options for water recycling. The various modes of reuse must be evaluated with respect to environmental repercussions and with respect to economic criteria. Water recycling is indeed one measure to enhance the efficiency of water use. On the other side, water reuse can also lead to environmental damages. For instance, the recycling of irrigation water into irrigation systems might lead to the salinization of the soil, thereby decreasing its fertility drastically. We will get to these kinds of quality problems in Sect. 3.10. The scheme in Fig. 3.8 depicts water reuse options in a rough manner. The civil engineering literature (such as Asano 1998) enlists a variety of reuse categories:

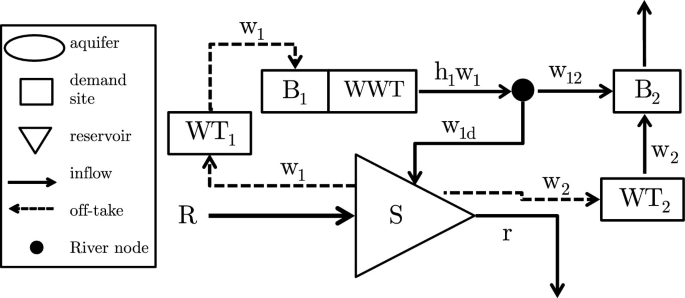

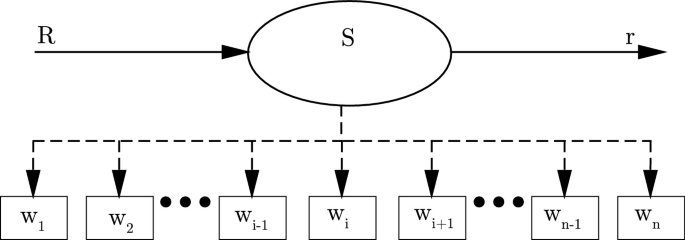

Water reuse, to whatever purpose, is part of IWRM. In its simplest form, water reuse follows from an optimal allocation procedure which takes into account return flows. Figure 3.9 shows a simple scenario for two users.

User 1 uses water \(w_1\) from a river or lake and returns a portion \(h_1 w_1\) . We assume that the quality of the returned water is such that the body of water, e.g., a lake or groundwater, maintains its environmental quality. The costs of necessary purification treatments (WWT) are included in the benefit function of user 1. Water \(w_\) used by user 1 needs treatment (WT1) that is associated with costs, which are assumed to be c per unit. User 2 is located at the same water reservoir. She uses return flows from user 1, which is denoted by \(w_\) , and diverts \(w_\) from the reservoir if she needs more than \(h_w_\) . Notice that water withdrawn by user 2, \(w_\) , also have to be treated at costs c per unit of water. If user 2 does not use the whole amount of return flow from user 1 the residual, \(w_\) , flows back into the water reservoir. To keep the model as simple as possible, we assume that user 2 returns no water. The respective dynamic balance for the water stock is

$$\beginSubstituting the definition of the residual flow

$$\begininto Eq. (3.38) yields

$$\beginThe model allows for both direct and indirect reuse. Exclusive indirect reuse is present if \(w_=0\) is true, which implies that all return flows flow back into the reservoir, i.e., \(w_=h_w_\) . If treatment costs occur, indirect reuse will of course be minimized because direct use avoids the additional treatment costs that accrue to \(w_2\) .

In the following, we derive the optimal allocation within our hydro-economic model. To concentrate on the allocational effects of the return flow, we disregard all the issues raised in the previous sections, i.e., fairness considerations or issues of poverty. We confine ourselves to the simple task of maximizing the aggregate benefit of both users. Let us assume that user 2 is relatively big compared to user 1, i.e., \(B^_(w) < B^_(w)\) . The optimization program is

$$\beginsubject to Eqs. (3.39) and (3.40). To keep the analysis simple, we disregard fixed costs by assuming that these costs are covered by access fees. Footnote 27 Also we assume that water is not scarce Footnote 28 which allows us to skip Eq. (3.40).

The KKT conditions are as follows:

$$\beginwhere \(\lambda \) is the Lagrangian to the constraint, which is given by Eq. (3.39). These conditions apply under the assumption that \(w_ > 0\) (else there would be no recycling in this model). Therefore, Eq. (3.42) applies with strict equality.

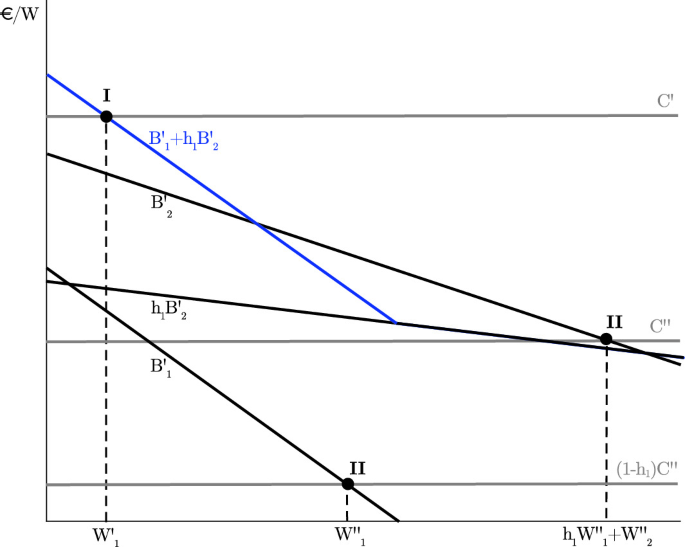

Figure 3.10 depicts the solutions for two cases. The first case (case I) refers to high water treatment costs, the second to relatively low costs (case II). The figure is drawn under the assumptions that the marginal benefits of both users are declining linearily with respect to water use, i.e., “ \(B_^(w) = a_-b_ w\) , and that user 1 is “small” in comparison to user 2, i.e., \(B_^(w)< B_^(w), \forall w \ge 0\) .

Before we take a closer look at these cases, let us first note that the waste of water, i.e., \(w_ > 0 \) , cannot be the result of the optimization program. It cannot be optimal to return a portion of clarified water \(h_ w_\) into the reservoir and withdraw it later with additional treatment costs. Footnote 29

Here we assume that the processing costs are very high. In order to make the importance of water recycling particularly visible, we also assume that without a technical infrastructure for water reuse, i.e., if the used water of user 1 cannot be transferred to user 2, none of the two users would take water from the reservoir. This case is depicted in the figure by the fact that the marginal cost line lies above both marginal benefits ( \(c^ > a_, i=1,2 \) ).

In case I, it follows from the optimality conditions that the optimal allocation is characterized by the following compact rule (rule I) Footnote 30 :

$$\beginThe weighted aggregated marginal benefits should be equated to the marginal treatment costs (see point I in Fig. 3.10). This equation is nothing else as the allocation rule for a public good. The water use of user 1, \(w_\) , exhibits the characteristics of a public good which serves twice as an input, the first time for user 1 and then the second time for user 2 diminished by factor \(h_\) . Point I in Fig. 3.10 is identified by equating the aggregated marginal benefits of both users of \(w_\) to marginal treatment costs.

If treatment costs are very low case II, which is represented by the two points II in Fig. 3.10, applies. The corresponding optimal allocation rule is (rule II):

$$\beginUser 1 diverts \(w_1\) . She equates her marginal benefit to marginal treatment costs related to the effective water use per liter, i.e., \((1-h_)\) (see the left one of the two points II in Fig. 3.10). User 2 is allocated the return flow of \(h_1 w_1\) and supplements her water consumption such that \(B'_(h_ w_ + w_) = c^\) . Therefore, total water use of user 2 is \(h_w_ + w_\) (see the right one of the two points II in Fig. 3.10). This rule is very well known from hydro-economic models that include return flows. Notice that this rule only applies if marginal water treatment costs are relatively low. Otherwise (case 1), we have to apply the rule for water as a public input (rule I).

Both rules are cost dependent special cases of the optimality conditions as derived in Eqs. (3.42)–(3.45), which are the result of a hydro-economic model optimizing aggregate benefits of both users.

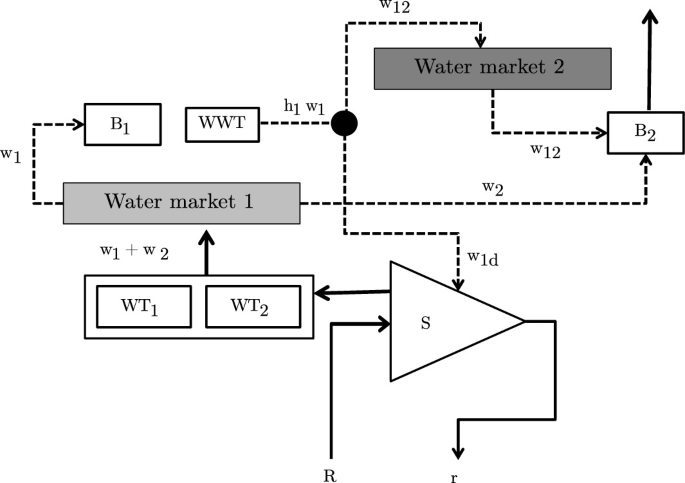

Let us take case II (low treatment costs) and assume that the institutional implementation of rule II should be accomplished by introducing a water market system, as depicted in Fig. 3.11. Footnote 31 Each user buys freshwater from the water treatment plants for a uniform price, \(p_\) . In addition, there is a market for recycled water, in which user 1 offers treated water whereas user 2 is on the demand side. The price in water market 2 is such that supply is equal to demand.

Let us assume that both markets operate under perfect competition or, alternatively, that a regulation authority sets prices close to a competitive market. Thus, both water treatment plants will offer water for a price equal to the marginal treatment costs, i.e., \(p_=c^\) .

User 1 buys water in market 1 and, at the same time, offers treated water in market 2 by solving the following optimization:

$$\beginAssuming that user 1 buys and sells water the KKT conditions are

$$\beginMerging both KKT equations yields

$$\beginUser 2 has the option to buy water in both markets, hence the corresponding optimization program is

$$\beginWe have assumed that \(p_=c^\) is so low that user 2 buys water in both markets ( \(w_>0 \,\text< and >\, w_>0\) ). Then the optimal water demand in both markets follows the rule:

$$\beginIf prices were to differ, the user would only operate in one of the two markets. Thus, in this scenario both prices are equal.

Both market participants set their marginal benefits equal to the respective prices. In turn \(p_\) is equal to marginal costs. If we put together this information by substituting prices in Eq. (3.51) by Eq. (3.53) and bear in mind that \(h_ w_ = w_ \) we get

$$\beginwhich is simply the optimality rule for case II (cf. Eq. (3.47)). The implementation of two water markets is able to replicate the optimal allocation derived in the framework of a central planning approach.

With the same approach, we can show that the system of two markets would also secure optimality in case I. Footnote 32 This is interesting because user 2 should only buy recycled water in market 2 and it is interesting because the sequential use of water makes water almost a public good. Footnote 33 It is a standard result from microeconomic textbooks or introductions to public economics that the private provision of public goods leads to a misallocation. Why not here? Users consume water one after the other and two markets are implemented (instead of only one market). The treatment plant sells water only to user 1 and user 1 sells to user 2. If then only the treatment plant sells water in market 1 to both users then both users could not afford the water in case I since \(B_^(w_) < c^\) (see Fig. 3.10). This market result is not optimal. The reason is that we have one market missing. Inserting the second market allows to implement the optimal allocation for public goods. This is due to the hydro-technological situation implicitly endowing user 1 with property rights. He can sell the water used and treated or let it return to the reservoir S. But he will sell the water after usage to user 2. There will be a positive price less than marginal costs \(c^\) that user 2 will accept.

Ecological Sanitation (EcoSan) is a concept standing for a potential change in the paradigm of wastewater disposal. Wastewater has been regarded only as a problem for a long time, because it involves hygienic hazards and contains organic matter and eutrophying substances in the form of nitrogen and phosphorus. These substances cause problems in seas, lakes, and streams. Due to inadequate sanitation, wastewater causes serious water-related issues in many parts of the world (e.g., Sub-Saharan Africa), as it has in the past on central Europe (e.g., cholera epidemic in Hamburg in 1892 with 8,600 deaths). However, in the framework of EcoSan the wastewater is seen as a reusable substance that contains valuable components, such as nutrients (nitrogen, phosphorous), sulfur, potassium, magnesium, and many trace elements essential for fertile soils.

The main idea of the EcoSan concept is to close the nutrient loop between sanitation and related sectors (e.g., agriculture) and hence it is quite more than simply gray water reuse or rainwater use. Closing the loop enables the recovery of organics, macro and micronutrients, water, and energy contained in wastewater and organic waste and their subsequent productive reuse mainly in agriculture, or for other reuse options. The main advantages are as follows (Werner et al. 2009):

This concept was applied in a number of pilot projects, for instance, in Lübeck-Flintenbreite, Germany, for 350 inhabitants. The installed system comprises a strict separation of blackwater (wastewater from the toilet), gray water and stormwater. Blackwater together with organic waste should be treated anaerobically (producing biogas for energy and heat production) (Langergraber and Muellegger 2005). Other exemplary early EcoSan pilot projects were implemented by the “Svanholm Community” in Denmark, the Ecological Village Björnsbyn in Sweden, Ås in Norway or the Solar-City Linz-Pichling in Austria (Fröhlich et al. 2003). In 2020, the start-up Finizio is planning to install a test equipment in the (German) city of Eberswalde (https://finizio.de/produkte/).

Source: Fröhlich et al. (2003), Werner et al. (2009)

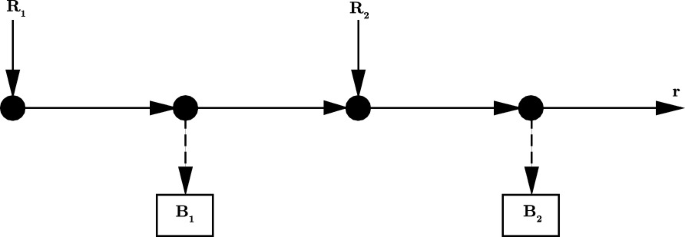

A simple example of a river with two users is given in Fig. 3.12. The upstream user 1 and the downstream user 2 compete for the water resources and are able to generate net benefits, designated by \(B_1(w_1)\) and \(B_2(w_2)\) , depending on the diverted water amounts, \(w_1\) and \(w_2\) . Furthermore, the river is fed by two inflows from headwater areas, that are located upstream of the tapping points of user 1 and user 2, respectively. These inflowing water quantities are denoted by \(R_1\) for user 1 and by \(R_2\) for user 2. The amount of water that leaves the addressed river system, i.e., the outflow, is represented by variable r.

Based on the IWRM approach, the objective to maximize net benefits in the total river basin is formulated as presented in Eq. (3.55).

$$\beginAny consumer can divert at most those quantities of water that are available at the respective tapping point, thus the constraints are given by Eqs. (3.56) and (3.57)

$$\beginOf course, if a minimum outflow quantity ( \(r_0\) ) of the addressed river system should be guaranteed, it is important to consider the additional constraints in Eq. (3.58), which ensures that the realized outflow r is equal or higher the obligatory minimum outflow \(r_0\) . The realized outflow is the water amount which is left in the river by both users. Therefore, it results from the difference between the headwater inflows and the abstraction amounts which means that \(r=R_1 + R_2 - w_1 - w_2\) . Therefore, we are able to formulate following condition for addressing the minimum outflow quantity:

$$\beginBased on the model formulated here, which corresponds to a maximization problem with the objective stated in Eq. (3.55) subject to the constraints defined in Eqs. (3.56) to (3.58), the KKT conditions can be derived:

$$\beginIt is likely that water will be diverted from the river as much as possible by the users, so that all available resources in the river are abstracted completely. This means that the outflow of the addressed river system, r, must not exceed the required outflow level, \(r_0\) , which implies \(r=r_0\) . Furthermore, the usable amount of water, given by \(R_1 + R_2 - r_0\) , has to be diverted entirely, thus the equality \(R_1 + R_2 - r_0 = w_1 + w_2\) holds. Based on these relations, it follows from the KKT conditions, that

To conclude: if \(r_0>0\) it follows that \(\lambda _r \ge 0\) and \(\lambda _2=0\) , while if \(r_0=0\) it follows that \(\lambda _r\) does not exist and \(\lambda _2 \ge 0\) .

By addressing Eq. (3.60) it follows that

Therefore the formulated conditions reduce to Eqs. (3.65) and (3.66). Footnote 35

$$\beginBased on the formulas displayed in Eqs. (3.65) and (3.66), it is possible to define optimality conditions for two different cases:

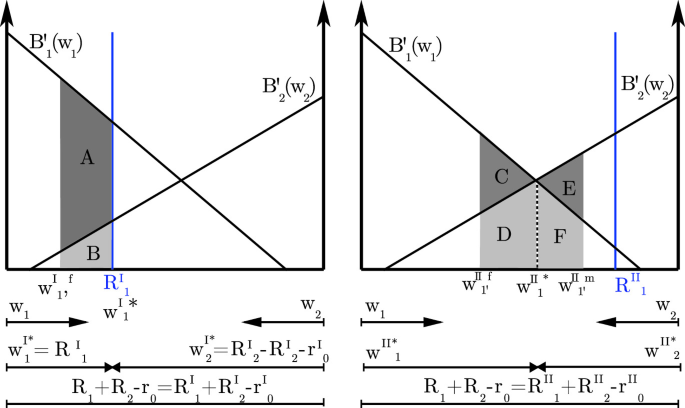

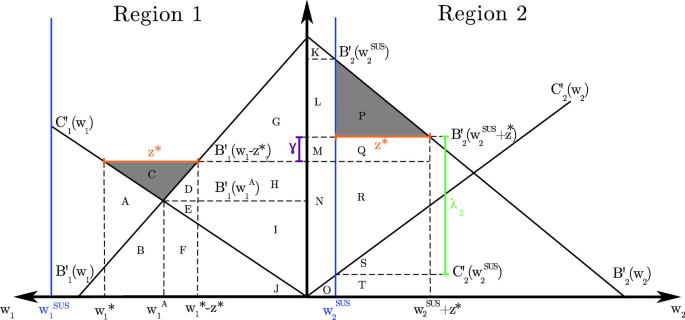

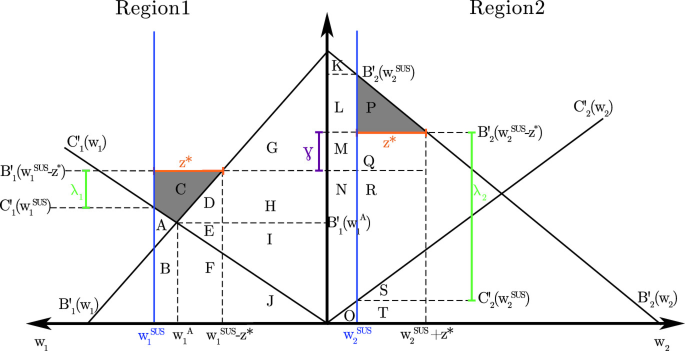

The optimal case depends mainly on the headwater inflows further upstream of the the tapping points of the consumers. Figure 3.13 displays two scenarios, I and II, whereas both are subject to the same outflow requirements, such that \(r_0=r_0^=r_0^\) , and they are restricted to the same amounts of useable water, i.e., \(R_1+R_2-r_0=R_1^+R_2^-r_0^=R_1^+R_2^-r_0^\) . The amounts of useable water are represented by the lengths of the horizontal axes of both plots in Fig. 3.13. The diversions of water by both users are illustrated by the arrows segmenting the horizontal axes, respectively. The diversion of the upstream user \(w_1\) is illustrated from the left point of origin of the diagram to the right, while in contrast the diversion of the downstream user \(w_2\) is pictured from the right point of origin to the left.

Scenario I is characterized by the fact that the natural inflow before the upstream user 1 is low and the natural inflow before the downstream user 2 is high. This scenario is visualized in panel (a) of Fig. 3.13, where the inflow to user 1, \(R_1^I\) , is located to the left of the intersection between the marginal benefit functions \(B_1'(w_1)\) and \(B_2'(w_2)\) . Compared to scenario I, the opposite situation is defined in scenario II (see panel b) in Fig. 3.13. Footnote 36 The headwater inflow before the upstream user, \(R_1^\) , is located to the right of the intersection point between the marginal benefit functions \(B_1'(w_1)\) and \(B_2'(w_2)\) in the plot.

Hence for scenario I, optimality can only be assured by case 1 in which the upstream user fully diverts the available water at his/her tapping point, therefore the optimal amount of water diverted by the upstream user is equal to the inflow to the upstream player, \(w_1^=R_1^\) . In that case, the downstream user does not receive any water inflows from the upstream user. It follows that user 2 can divert the difference between the downstream headwater inflows and the necessary outflows, thus the downstream user’s optimal amount of diverted water is defined by \(w_2^ = R_2^-r_0^\) . The required optimality condition of case 1 is fulfilled, because the marginal benefit of user 1 exceeds the one of user 2 for this allocation regime, i.e., \(B_1'(R_1^) > B_2'(w_2^) = B_2'(R_2^-r_0^)\) .

In scenario II (relative high upstream inflows \(R_1\) ), however, if the upstream user 1 diverts its total upstream headwater inflows (case 1), \(w_1^=R_1^\) , the resulting marginal benefit of the upstream user 1 falls below the one of the downstream user 2, i.e. \(B_1'(R_1^) < B_2'(w_2^) = B_2'(R_2^-r_0^)\) , which is illustrated on the right-hand side of Fig. 3.13. This is a violation of the optimality condition, case 1 is, therefore, the nonoptimal case, while the optimal allocation can only be implemented in case 2. To realize an optimal allocation in the river basin, the quantity of water diverted by the upstream user 1, \(w_1^=w_1^\) , ensures that the marginal benefits of the upstream and downstream user are equal, such that \(B_1'(w_1^) = B_2'(w_2^) = B_2'(R_1^+R_2^-w_1^-r_0^)\) holds. The optimal water diversion by the upstream user, \(w_1^\) , is identical to the one implied by the intersection point between the two marginal benefit functions \(B_1'(w_1)\) and \(B_2'(w_2)\) in panel (b) of Fig. 3.13, and the resulting optimal diversion by the downstream user 2 is characterized by \(w_2^ = R_1^+R_2^-w_1^-r_0^\) . If the upstream user diverts smaller amounts than optimal, where \(w_1^ = w_1^ < w_1^\) , the downstream user can consume more water than in the optimal case, thus \(w_2^ = R_1^+R_2^-w_1^-r_0^ > w_2^\) .

The corresponding welfare effects are depicted on the right-hand panel in Fig. 3.13, while the welfare gains of downstream user 2, represented by area D, are much smaller than the welfare losses upstream user 1 incurs, displayed by the areas C and D. Hence there is a loss of social welfare equal to area C, if real upstream diversion falls below the optimal upstream extraction.

Similarly, if the upstream user 1 diverts more quantities than optimal, i.e. \(w_1^ < w_1^= w_1^ \le R_1^\) , less amounts of water are available for the downstream user 2 compared to the optimal allocation regime, thus \(w_2^ = R_1^+R_2^-w_1^-r_0^ < w_2^\) . The corresponding welfare losses for the downstream user 2 cover the areas E and F and thus outweight the corresponding welfare gains for the upstream user 1, which cover the area F. This results in a loss of social welfare equal to area E due to that kind of deviation from the optimal allocation regime.

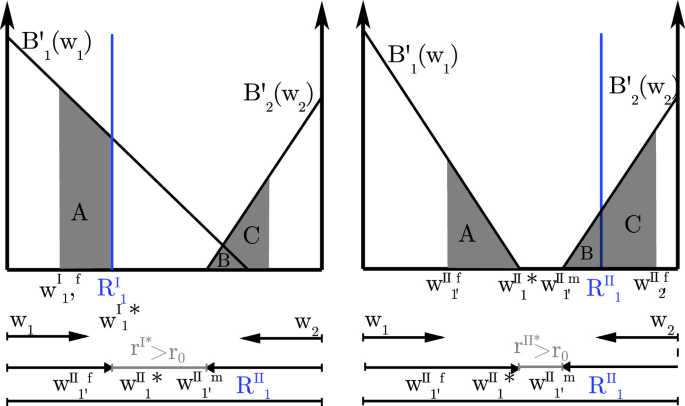

In the former analysis, water was assumed to be a scarce resource in a river basin and the useable amounts were completely diverted by the users. With respect to the allocation of the water resources, a trade-off exists between the users. The more water one user diverts, the less the other user is able to consume. This trade-off concerning the water resource is not relevant for the downstream user whose water supply is non-scarce/abundant, but if the useable amounts must not be entirely allocated among the users, the inequality \(R_1+R_2-r_0 \ge w_1+w_2\) will be a relevant constraint to the optimization problem. Therefore, the outflow from the river basin can exceed the minimum outflow requirements, i.e., \(r \ge r_0\) . From the KKT conditions, displayed in Eqs. (3.59) to (3.63), it follows that \(B_2'(w_2)=\lambda _2=\lambda _r=0\) holds. Footnote 37 This implies for the optimal case that the downstream user has to consume at his/her saturation level, which corresponds to the null of its marginal benefit function, i.e., \(B_2'(w_2*)=0\) . The user 2 chooses its optimal diversion, \(w_2^*\) , in such a way that its marginal benefit becomes zero, i.e., \(B_2'(w_2^*)=0\) . For user 1, it is possible to derive algebraic characterizations of the optimality conditions from the KKT conditions, which are displayed in Eqs. (3.67) to (3.68).

$$\beginSimilar to the situation with water scarcity, it is possible again to define optimality conditions for two different cases:

Which of the two cases is suitable to implement optimality depends on the scarcity situation of the upstream user. Illustrative examples with two different scenarios are pictured in Fig. 3.14. In the plot for scenario I, depicted in panel (a) in Fig. 3.14, the intersection between the upstream headwater inflows, \(R_1^I\) , and the marginal benefit function of the upstream user, \(B_1'(w_1)\) , is characterized by a positive marginal utility for the upstream user. Hence water is scarce for the upstream user in case 1 I. If user 1 passes a limited quantity of water downstream, as in case 2, the possible domain of consumption will be \(w_1^I \in [0, R_1^I]\) . The marginal benefit function, \(B_1'(w_1^I)\) , does not become zero for any \(w_1^I\) of the defined domain. Hence there is a violation of the optimality condition for case 2 and it follows that case 1 should be the optimal one. In case 1, the upstream headwater inflows are fully consumed, i.e., \(w_1^=R_1^\) . The optimality condition of case 1 is fulfilled because the marginal benefit of the upstream user is positive for this optimal consumption level, such that \(B_1'(R_1^) \ge 0\) .

In contrast to scenario I, water is not scarce for the upstream user 1 in scenario II, as displayed in panel (b) in Fig. 3.14, where the upstream headwater inflow, \(R_1^\) , is located to the right of the saturation point characterized by \(B_1'(w_1) = 0\) in the plot. If the upstream user 1 entirely diverted the upstream headwater inflows, as in case 1 with \(w_1^=R_1^\) , its marginal benefit would be negative, which would violate the optimality condition of case 1. Limited quantities of upstream headwater inflows should, therefore, be passed downstream, hence \(R_1^ > w_1^\) as in case 2, and user 1 diverts the water quantities in such a way that its marginal benefit becomes zero. The optimality condition of this case 2 is guaranteed to be satisfied due to the assumptions made, hence the optimal consumption, \(w_1^\) , is identical to the null of the marginal benefit function, i.e., \(w_1\) such that \(B_1'(w_1^) = 0\) , which means that the user 1 diverts the amount of water equal to its saturation point.

A loss of consumer surplus for upstream user 1 would result if the upstream user deviated from the optimal amount to be diverted, so that \(w_1^ < w_1^\) as well as \(w_1^ < w_1^\) . This loss is represented by the area A in Fig. 3.14. Similarly, a loss of consumer surplus for downstream user 2, illustrated by the areas B and C, will also occur if the diverted amount of user 2 falls below its saturation quantity. Both types of deviations from the optimal allocation generate losses in social welfare.

Rainwater harvesting is a technique for providing water that has been used since ancient times. For example, Roman cities were designed and built such that the inhabitants could collect rainwater for drinking and domestic purposes. But captured rainwater can also be used for irrigation in the agricultural sector or in urban areas to provide water for the non-potable uses like a toilet flushing. One distinct advantage of rainwater harvesting is that it can be shaped in a decentralized manner, e.g., simple roof water collection systems. But also bigger projects are conceivable. In the Global South, land surface catchment systems are implemented in many rural areas. They can be used for irrigation systems or simply as a method to recharge the local groundwater. Since the technique is rather simple, rainwater harvesting investments are an integral part of rural development programs. All in all, it seems to be a highly efficient method to provide people with more water without stressing the water cycle.