This year, Congress will consider what may be the biggest tax bill in decades. This is one of a series of briefs the Tax Policy Center has prepared to help people follow the debate. Each focuses on a key tax policy issue that Congress and the Trump administration may address.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) made several changes to the tax code intended to increase health insurance coverage, reduce health care costs, and finance health care reform. On net, these taxes and credits are projected to reduce the deficit by $46 billion in 2020, the first year all ACA tax provisions are scheduled to be in effect. Taken together, they increase the average tax burden significantly for families in the top 1 percent of the income distribution but benefit families in the bottom income quintiles by providing new credits that, on average, exceed their new taxes. Combined with the ACA’s Medicaid expansion, the coverage-related taxes are projected to reduce the number of uninsured by 23 million in 2020.

To increase health insurance coverage, the ACA provides a tax credit for individuals and small employers to purchase insurance and imposes excise taxes on individuals without adequate coverage and on employers who do not offer adequate coverage. To reduce health care costs and raise revenue for insurance expansion, the ACA imposes an excise tax on high-cost health plans. To raise additional revenue for reform, the ACA imposes surtaxes on high-income families; excise taxes on health insurers, pharmaceutical companies, and manufacturers of medical devices; and higher thresholds for the income tax deduction of medical expenses.

ACA tax provisions include the following:

Taken together the ACA taxes and credits are projected to reduce the budget deficit by $46 billion in 2020. The ACA’s revenue raisers more than cover the cost of the PTC and the small employer health insurance credit and pay for part of the cost of expanding Medicaid, projected to be $91 billion in 2020. The ACA, which the Congressional Budget Office estimated would reduce the budget deficit, primarily covers the remaining Medicaid costs by reducing Medicare payments to providers and to Medicare Advantage plans.

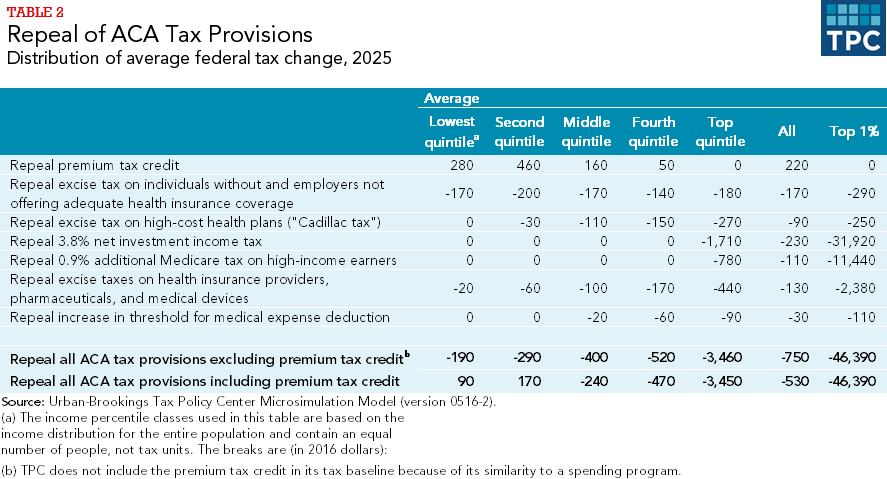

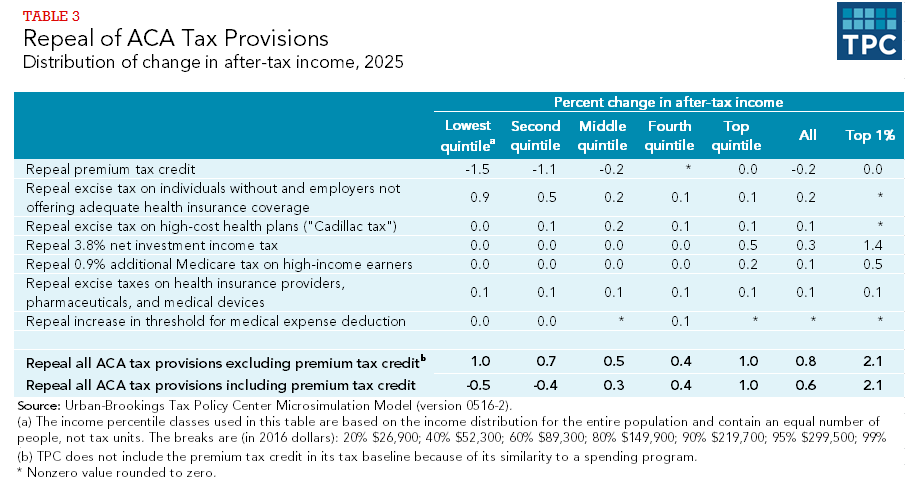

On net, the ACA significantly increases average taxes on families in the top 1 percent of income, cuts taxes on families in the bottom two quintiles, and modestly increases taxes on the rest of families. Repealing the ACA taxes (including credits) in 2025 would provide an average tax cut of $46,000 to families in the top 1 percent, increasing their after-tax incomes by more than 2 percent (tables 2 and 3). In contrast, average taxes for families in the bottom and second quintiles would increase by $90 and $170, respectively, reducing their average after-tax incomes by at least 0.4 percent. Families in the middle quintile would receive an average tax cut of $240, increasing their after-tax incomes by 0.3 percent.

While repealing ACA taxes would hurt families in the bottom two quintiles on average, the story is more complicated. For the 6 percent of families in the bottom quintiles with PTCs, repealing ACA taxes would be a substantial loss, over $5,000 on average (table 4). But most low-income families would receive a modest tax cut of around $250. And tax cuts would be larger—averaging about $1,500—for the 11 percent of low-income families affected by the coverage-related excise taxes (not shown).

Tax changes are an essential component of the package of reforms enacted by the ACA. Policymakers wishing to repeal or replace the ACA will need to make tax policy decisions that dramatically affect health insurance coverage, the budget deficit, and the distribution of after-tax income.